Is Inflation About to Make a Comeback?

Taking a look at recent data, analysis, and influential commentary - Article #51

In this 12-minute article, The X Project will answer these questions:

I. Why this article now?

II. What are the deflationary vs. inflationary forces, and who are they impacting?

III. What does Jamie Dimon have to say?

IV. What do the latest CPI reports tell us?

V. What is the scariest chart in global macro right now?

VI. What are other industrial metal prices doing?

VII. Was 2021-23 just the first wave of long-term inflation?

VIII. What did Fed Chair Powell say this week?

IX. What does The X Project Guy have to say?

X. Why should you care?

Reminder for readers and listeners: nothing The X Project writes or says should be considered investment advice or recommendations to buy or sell securities or investment products. Everything written and said is for informational purposes only, and you should do your own research and due diligence. It would be best to discuss with an investment advisor before making any investments or changes to your investments based on any information provided by The X Project.

I. Why this article now?

This article is being written now mainly because of the data, analysis, and influential commentary that have come out in the past two weeks. Each of the next seven sections is a reason for writing this article now. Furthermore, some markets and several of the investment themes to which The X Project subscribes have reacted as expected, providing additional confirmation of inflationary expectations. I’ll get into that more in the last two sections for paid subscribers, but it is timely to review all of this so investors can consider making appropriate adjustments to their portfolios if need be.

II. What are the deflationary vs. inflationary forces, and who are they impacting?

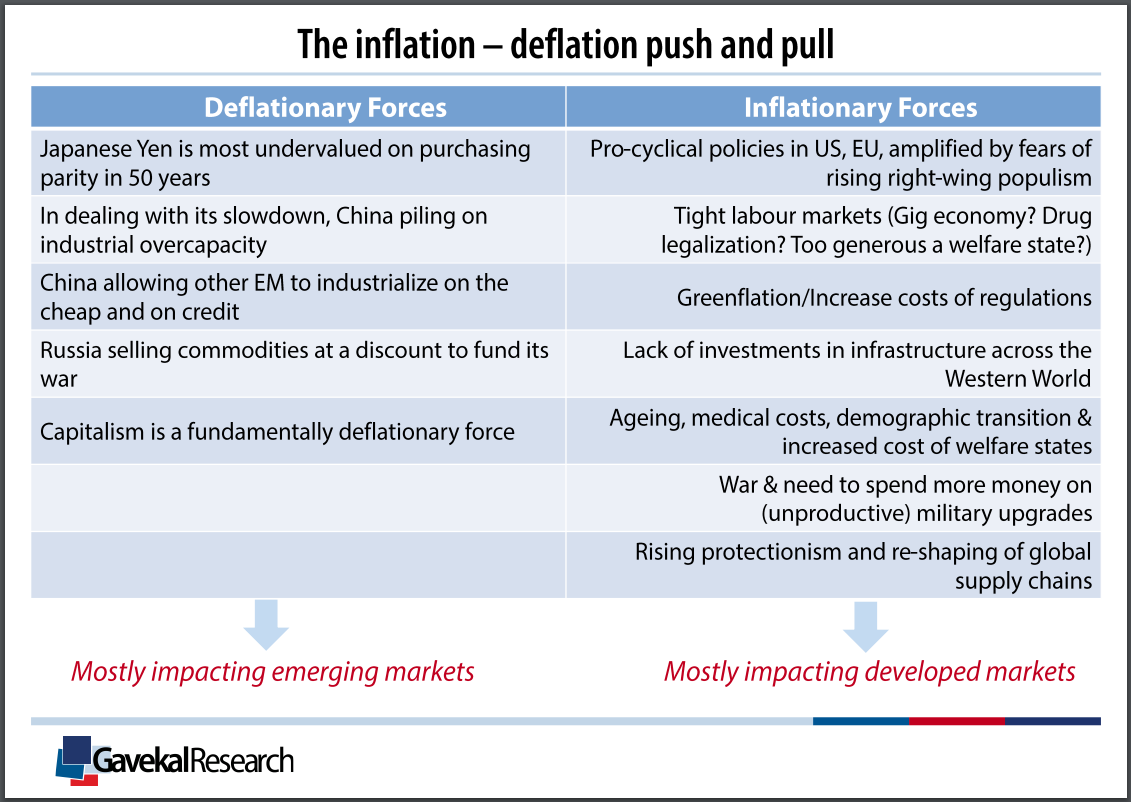

Louis-Vincent Gave is a founding partner and CEO of Gavekal, a financial services company organized around three key activities: financial research for institutional investors, funds and private wealth management, and portfolio construction tools. Last week, he shared a recording of a Webinar he hosted with the two other founding partners of Gavekal titled “Forward to the 1970s? Investing for An Inflationary Age.” There was a lot of content in the hour-long recording and the three information-packed presentation decks they each prepared but did not actually present. I will cover more of that content in another article soon, but slide 20 from Louis-Vincent’s presentation is a good one to kick off this article:

A week ago, The X Project published “What About the Possibility of Deflation?” in which deflationary arguments were considered despite concluding that inflation was the far greater immediate threat. The only overlapping deflationary argument in that article was China. Still, Gavekal’s take on China’s deflationary force is somewhat different. A very insightful point of Gavekal’s deflationary forces listed is that they are “mostly impacting emerging markets,” whereas the inflationary forces are “mostly impacting developed markets.”

III. What does Jamie Dimon have to say?

JPMorgan Chase & Co.’s Annual Report includes a letter to shareholders from its Chairman and CEO, Jamie Dimon, who is perhaps a modern-day version of John Pierpont Morgan himself. As the leader of America’s largest bank that still carries Morgan’s name, Jamie Dimon is someone to whom you want to listen and pay attention when he speaks or, in this case, writes. On the topic of inflation, here is what he has to say in the letter to shareholders dated April 8, 2024:

“We have ongoing concerns about persistent inflationary pressures and consider a wide range of outcomes to manage interest rate exposure and other business risks.

Many key economic indicators today continue to be good and possibly improving, including inflation. But when looking ahead to tomorrow, conditions that will affect the future should be considered. For example, there seems to be a large number of persistent inflationary pressures, which may likely continue. All of the following factors appear to be inflationary: ongoing fiscal spending, remilitarization of the world, restructuring of global trade, capital needs of the new green economy, and possibly higher energy costs in the future (even though there currently is an oversupply of gas and plentiful spare capacity in oil) due to a lack of needed investment in the energy infrastructure. In the past, fiscal deficits did not seem to be closely related to inflation. In the 1970s and early 1980s, there was a general understanding that inflation was driven by “guns and butter”; i.e., fiscal deficits and the increase to the money supply, both partially driven by the Vietnam War, led to increased inflation, which went over 10%. The deficits today are even larger and occurring in boom times — not as the result of a recession — and they have been supported by quantitative easing, which was never done before the great financial crisis. Quantitative easing is a form of increasing the money supply (though it has many offsets). I remain more concerned about quantitative easing than most, and its reversal, which has never been done before at this scale.

Equity values, by most measures, are at the high end of the valuation range, and credit spreads are extremely tight. These markets seem to be pricing in at a 70% to 80% chance of a soft landing — modest growth along with declining inflation and interest rates. I believe the odds are a lot lower than that. In the meantime, there seems to be an enormous focus, too much so, on monthly inflation data and modest changes to interest rates. But the die may be cast — interest rates looking out a year or two may be predetermined by all of the factors I mentioned above. Small changes in interest rates today may have less impact on inflation in the future than many people believe.

Therefore, we are prepared for a very broad range of interest rates, from 2% to 8% or even more, with equally wide-ranging economic outcomes — from strong economic growth with moderate inflation (in this case, higher interest rates would result from higher demand for capital) to a recession with inflation; i.e., stagflation. Economically, the worst-case scenario would be stagflation, which would not only come with higher interest rates but also with higher credit losses, lower business volumes and more difficult markets. Under these many different scenarios, our company would continue to perform at least okay. Importantly, being prepared means we can continue to help our clients no matter what the future portends.”

In another section, he also says this:

“It's hard to see certain long-term trends, but you must try.

There is too much emphasis on short-term, monthly data and too little on long-term trends and on what might happen in the future that would influence long-term outcomes. For example, today there is tremendous interest in monthly inflation data, although it seems to me that every long-term trend I see increases inflation relative to the last 20 years. Huge fiscal spending, the trillions needed each year for the green economy, the remilitarization of the world and the restructuring of global trade — all are inflationary. I’m not sure models could pick this up. And you must use judgment if you want to evaluate impacts like these.”

IV. What do the latest CPI reports tell us?

The Bureau of Labor Statistics released the March 2024 Consumer Price Index figures on April 10, 20204. Here are the headline numbers in the way they are typically reported:

March CPI MoM 0.4%; Estimated 0.3%; Previous 0.4%

March CPI YoY 3.5%; Estimated 3.4%; Previous 3.2%

March Core CPI MoM 0.4%; Estimated 0.3%; Previous 0.4%

March Core CPI YoY 3.8%; Estimated 3.7%; Previous 3.8%

Ok, given that all four numbers came in “hotter” or higher than expected or estimated, the stock market reacted negatively on April 10, with the S&P 500 closing 1% lower that day. However, only one number came in higher than the previous month. So, what does this tell us about the recent trend? As listed above, not much.

Analysts like to look at moving averages to get a sense of trends. This chart (shared by

on X/Twitter) shows the 3 and 6-month annualized percent change in Core CPI, which excludes food and energy, which is at 4.53% and 3.94%, respectively:As you can see, the 3-month average has been trending higher since August 2023, and the 6-month average has also done likewise since November 2023. As such, the stock market’s realization that the Fed will likely not be able to cut interest rates as soon or as much as it had previously hoped is a big reason why the market has been weak and generally selling off in the week and a half since the latest CPI numbers came out.

V. What is the scariest chart in global macro right now?

According to Andreas Steno Larsen (@AndreasSteno on X/Twitter), CEO at Steno Research (macro, investing, and geopolitics) and host at Real Vision and the “Macro Sunday” and “Store Penge” podcasts, this is the scariest chart in global macro right now:

The chart is titled “Price Pressures vs. Copper,” with the sub-title of “Dr. Copper hints of a return to service price pressures.” It shows the tight correlation between the price of copper and the ISM Services Business Prices Index since 2007 and the divergence that began in late 2022, with copper staying elevated and recently increasing while the ISM Services Business Price Index started falling and did so even more recently. What is scary about it is the inflationary impact if the ISM Services Business Price index starts rising to close the gap and re-establish the historical correlation.

VI. What are other industrial metal prices doing?

On April 17th, @NorthstarCharts on X/Twitter posted these charts:

Tin futures breaking out:

Zinc futures breaking out:

Nickel futures breaking out:

Aluminum futures breaking out:

VII. Was 2021-23 just the first wave of long-term inflation?

Anatole Koletsky is another founder of Gavekal and presented in the same webinar referenced in Section II above. Slide 8 from his presentation asked the question:

As you can see in the chart, the period from 1958 to 1982 started with eight years of low and stable inflation, followed by a first wave of inflation that peaked in 1970-71, a second wave in 1975, and a third wave in 1980-81. Given everything covered in this article, the suggestion that we follow a similar pattern seems pretty reasonable.

In the next section, I will explain what Jerome Powell said this week. In Section IX, I will tell you what I think about all of this. And then in Section X, why you should care and, more importantly, what more you can do about it. However, I have just hit a new paid subscriber threshold, so you must now be a paid subscriber to view the last three sections. The X Project’s articles always have ten sections. Soon, after a few more articles, the paywall will move up again within the article so that only paid subscribers will see the last four sections, or rather, free subscribers will only see the first six sections. I will be moving the paywall up every few weeks, so ultimately, free subscribers will only see the first four or five sections of each article. Please consider a paid subscription.

All paid subscriptions come with a free 14-day trial; you can cancel anytime. Every month, for the cost of two cups of coffee, The X Project will deliver two articles per week ($1.15 per article), helping you know in a couple of hours of your time per month what you need to know about our changing world at the interseXion of commodities, demographics, economics, energy, geopolitics, government debt & deficits, interest rates, markets, and money.

You can also earn free paid subscription months by referring your friends. If your referrals sign up for a FREE subscription, you get one month of free paid subscription for one referral, six months of free paid subscription for three referrals, and twelve months of free paid subscription for five referrals. Please refer your friends!