Trade Wars are Class Wars: How Rising Inequality Distorts the Global Economy and Threatens International Peace

A summary of the book written by Matthew C. Klein and Michael Pettis (2020) - Article #20

In this 20 min article, The X Project will answer these questions:

I. Why this book, and what’s it about?

II. Who is the author?

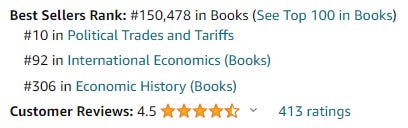

III. How popular is the book?

IV. What is one of the top takeaways from the book?

V. What is another top takeaway?

VI. What is the third top takeaway?

VII. What is the fourth top takeaway?

VIII. What is the fifth top takeaway?

IX. What does The X Project Guy have to say?

X. Why should you care?

I. Why this book, and what’s it about?

Trade Wars Are Class Wars by Matthew C. Klein and Michael Pettis presents a compelling narrative reframing our understanding of global economic imbalances. The book argues that these imbalances are not merely the product of national policies but are rooted in the class divisions within countries. This provocative perspective is crucial for The X Project's readership, offering deep insights into the intersections of geopolitics and economics. Let's dive into why this book matters and what it's all about.

At its core, Trade Wars Are Class Wars posits that the massive trade imbalances destabilizing the world's economy result from policies that encourage wealth to be concentrated in the hands of the few. This concentration suppresses domestic consumption and pushes nations like China, Germany, and Japan to rely excessively on exports. The authors argue that these are not just trade wars between countries but, fundamentally, class wars within them. The rich in surplus countries save too much while the rest spend too little, leading to global economic tensions and a distortion of the free market. This narrative is especially pertinent for readers seeking to understand the deeper, often hidden, forces driving market fluctuations and policy decisions.

Klein and Pettis don't just diagnose the problem; they explore its profound implications on global financial stability, geopolitical tensions, and the future of economic growth. They dismantle the traditional view that trade imbalances result from differences in national cultures, preferences for saving over spending, or even the inherent advantages of certain economies. Instead, they place the blame squarely on policies that skew income distribution, thereby transforming macroeconomic problems into social and political crises. This perspective shifts the conversation from technical and economic debates to broader discussions about societal values and the role of government, making it a must-read for anyone interested in the deeper currents shaping our world.

II. Who are the authors?

According to Amazon, “Matthew C. Klein is the founder and publisher of The Overshoot, a premium subscription research service focused on the global economy, financial markets, and public policy. He was previously the Economics Commentator at Barron's, and has also written for the Financial Times, Bloomberg View, and the Economist. Before entering journalism, he was a research assistant at the Council on Foreign Relations and an investment associate at Bridgewater. Originally from Chicago, he lives in San Francisco.”

According to Wikipedia, Michael Pettis is an American professor of finance at Guanghua School of Management at Peking University in Beijing and a nonresident senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Pettis began his career in 1987, joining Manufacturers Hanover (now JPMorgan Chase) as a trader in the Sovereign Debt group. From 1996 to 2001, he was at Bear Stearns as a managing director-principal in Latin American capital markets. Pettis also served as an advisor to sovereign governments on topics regarding financial management, including the governments of Mexico, North Macedonia, and South Korea.

III. How popular is the book?

Here are the book’s rankings on Amazon:

IV. What is one of the top takeaways from the book?

History and distortions

As a student of macroeconomics and its history and having recently read The Silk Roads, I knew that global trade had been happening for a long time and generally growing throughout history. I did not know that world trade (total exports as a share of world output) did not surpass its 1873 peak until the 1970s. Of course, two World Wars and a Great Depression in between certainly make sense for why global trade retreated and stagnated for a century. And the takeaway from history is we could easily retreat from our recent peak of global trade, and it could be a long while before that peak is surpassed.

The other aspect I did not explicitly know or consider is how distorted recent trade data has become due to several factors. First, “statistics produced by customs offices attribute all of the value of the imported inputs to whichever country happens to ship the finished product.” (p.29) Before the advent of the modern shipping container in the 1970s, there was very little trade in intermediate goods, which are inputs to the final finished product. Today, there are three major transnational manufacturing networks: The United States with Canada and Mexico; Germany with Czechia, Hungary, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, Portugal, and Spain; and China with Korea and Taiwan. “Economists have recently begun producing alternative trade statistics that account for these transnational manufacturing networks. For the United States, imports are overstated by about 16 percent while exports are overstated by about 20 percent. Chinese imports and exports are both overstated by about 30 percent.” (p.29)

The growth of transoceanic shipping among the three main manufacturing networks adds to the distortions of trade data. The location of oceanic ports such as Belgium, The Netherlands, Hong Kong, and Singapore therefore exaggerate figures on exports and imports for those countries.

Lastly, potentially most significantly, is corporate tax avoidance by companies participating in international trade. In the mid-1990s, large US companies paid an effective tax rate of over 35 percent. As foreign sales rose and companies got better at shifting profits to lower-tax jurisdictions, their effective tax rate dropped to about 30 percent by the early 2020s and to roughly 26 percent by the mid-2010s. “These profit shifts have done strange things to the official figures on trade and investment, especially as companies have transferred more and more of the value of what they produce into intangible assets. About 40 percent of all profits earned by multinational corporations outside their home markets are shifted from high-tax jurisdictions, such as China, France, Germany, Japan, and the United States, into low-tax jurisdictions, such as the Cayman Islands, Ireland, and Singapore. Exports from the high-tax countries are artificially depressed, imports are artificially elevated, and profits earned from subsidiaries in corporate tax havens are unreasonably large.” (p.32-33)

The takeaway here is that standard trade data is filled with misinformation. Understanding the world economy by studying trade independently is no longer possible and requires understanding how money moves across borders. The net result is financial imbalances now determine trade imbalances, but we need to understand the remaining takeaways below for this statement to make sense.

V. What is another top takeaway?

The Growth of Global Finance and Macro Econ 101

The next important aspect Klein and Pettis covered is the growth of global finance. “As recently as 1855, the total value of cross-border financial claims was just 16 percent of one year of global economic output. By 1870, however, that figure had jumped to 94 percent. Today (2017), it is over 400 percent.” (p.41) The authors then devote a chapter to explain 200 years’ worth of credit booms and busts to prove that international financial flows do NOT consist mostly of trade finance but are instead driven by changes in credit conditions and speculative sentiment.

Understanding international financial flows requires an understanding of macroeconomics, and the authors provide an excellent tutorial on the subject by applying the fundamentals, which can be expressed in a few equations, to the real world to explain what is happening and why:

“Global Demand = Global Production

Demand = Consumption + Investment

Production = Consumption + Savings

Domestic Demand = GDP + Imports - Exports

Exports - Imports = Domestic Savings - Domestic Investment” (p.67)

“Investment = GDP + Imports - Consumption - Exports” (p.68)

The words that make up the equations are simple enough. Still, for those new to macroeconomics, the concepts and understanding are not as simple as there are whole books and courses or series of courses to fully educate you on the subject. So, for now, trust that these equations are not only true but must always be true based on the facts that globally, all economic output is either consumed or used to develop productive assets. For the world as a whole, saving and investment are equal by definition.

How is this all tracked and accounted for? According to Investopedia, the balance of payments (BOP) is the method countries use to monitor all international monetary transactions in a specific period. The BOP is usually calculated every quarter and every calendar year. All trades conducted by both the private and public sectors are accounted for in the BOP to determine how much money is going in and out of a country.

The BOP is divided into three main categories: the current account, the capital account, and the financial account. The current account marks the inflow and outflow of goods and services into a country. Earnings on investments, both public and private, are also put into the current account. The capital account is where all international capital transfers are recorded. This refers to the acquisition or disposal of non-financial assets (for example, a physical asset such as land) and non-produced assets, which are needed for production but have not been produced, such as a mine used to extract diamonds. In the financial account, international monetary flows related to investment in business, real estate, bonds, and stocks are documented. Also included are government-owned assets, such as foreign reserves, gold, special drawing rights (SDRs) held with the International Monetary Fund (IMF), private assets held abroad, and direct foreign investment. Assets owned by foreigners, private and official, are also recorded in the financial account.

Now that you know global finance has exploded in recent decades and you have a basic understanding of macroeconomics 101, we can move on to the next important point of the book.

VI. What is the third top takeaway?

The issue is a “saving glut”

Some of you may recall Ben Bernanke bringing attention to the issue of a “saving glut” in 2005 before he became the Federal Reserve Chairman. So what is a “saving glut”?

Above, in Section V, it was stated that saving and investment are equal by definition for the world as a whole. That said, saving and investment are not equal in most countries. “This has been the defining problem of the past few decades: people in certain countries are spending too little and saving too much.” (p.67) “This imposes an untenable choice for the rest of the world: absorb the glut through additional spending (saving less) or endure a slump caused by insufficient global demand.” (p.68) “It is obvious that consumption cannot grow with investments to produce more of what people want. It is less obvious, but just as important, that those investments require rising consumption to be profitable. Building truck factories or apartment complexes or power plants is not ‘investing’ in any meaningful sense if nobody ends up buying more trucks, living in the apartments, or needing the extra electricity. It is just waste. This explains how the world can be afflicted by a savings glut without having a high saving rate” (p. 80)

Which countries are producing this saving glut? All current account surplus nations, including, among others, Japan, the Netherlands, South Korea, Switzerland, and Singapore, contribute to the saving glut. The biggest contributor, however, is China, and the authors devote a thirty-page chapter to understanding China’s surplus. China followed the “high savings” instead of the “high wages” developmental model, and the Chinese version had four stages: “Reform and Opening Up” from 1978 to 1989, the Chinese Development Model from 1989-2008, From High Investment to Overinvestment 2008-2018, and The Spirit of ‘78 from 2018 onwards. Perhaps The X Project will go into the details of China’s economic rise at another time. Still, for this article, the main takeaway is that China produced excessively high savings as China’s GDP grew far faster than the living standards of the Chinese people. The share of GDP consumed by Chinese households fell by 15% between the late 1980s and the bottom in 2010. As of 2018, Chinese households consume less than 40% of Chinese output - a lower ratio than in every other major economy globally. This is a deliberate, known, and planned outcome of Chinese policies that favor the CCP party and other elites over Chinese workers and everyone else - a classic class war.

The second largest contributor to the global saving glut is Germany, which the authors devote a forty-three-page chapter to explain. With the fall of the Soviet Union and the Berlin Wall, more than 100 million people were liberated from communist regimes and integrated into Western Europe’s capitalist economy. The main takeaway is that the costs of German reunification were not initially apparent and ended up being higher and not anticipated. “German businesses were able to avoid the stagnation in their home market by selling to customers in other countries. Profits rose dramatically as costs (wages) held steady and export revenues rose in line with global growth. German underspending generated surplus income that was used to accumulate foreign financial assets, which in turn supported foreign demand for German exports and boosted corporate profitability. Germany’s increasingly unequal distribution of income effectively transferred purchasing power from German workers to consumers in the rest of the world.” (p. 160)

In the aftermath of the financial crisis of 2008, Germany successfully pushed the rest of Europe through austerity to become more like Germany, which continues to exacerbate the saving glut. “The deficit countries collectively shifted toward surplus, but for a variety of reasons, spending in Europe’s existing surplus countries - most notably Germany and the Netherlands - did not increase relative to production. There was no rebalancing within Europe. Instead, the rest of the world, mainly emerging markets in Africa, the Middle East, India, Indonesia, and Latin America, as well as the United Kingdom and United States, ended up being forced to absorb the resulting financial outflows through rising trade deficits and rising debt.” (p.172)

There are two takeaways from the saving glut. First, “the biggest mistake is to think that higher saving causes additional investment. Yes, restricting consumption frees up workers, machines, and material inputs. In times of scarcity, saving more is therefore a prerequisite for investing more… But there is nothing automatic about this process. Rather, it is contingent on specific economic conditions. When those economic conditions do not apply, higher saving simply means lower living standards.” (p. 80) Second, the net result of the saving glut is financial imbalances now determine trade imbalances.

VII. What is the fourth top takeaway?

The Exorbitant Burden and the Persistent Current Account Deficit

As everyone knows, the US Dollar is the global reserve currency, which has been called the United States’ exorbitant privilege. The X Project will tackle this as another topic another time. For this discussion, it is important to first understand that there are economic similarities between the US and Germany that the authors flesh out when questioning why the US is not a current account surplus nation. The answer is that if the US Dollar were not the global reserve currency and the US was not home to the world’s largest and best economy with the deepest and most liquid financial markets, then the US would be a current account surplus nation.

However, the aggregate result of the choices of savings and spending among American households, businesses, and the government is determined outside of America’s borders. “Foreign central banks and other reserve managers spent about $4.1 trillion buying dollar-denominated assets between the start of 1998 and the middle of 2008. This was in addition to Americans’ own purchases of dollar assets during this period, as well as those of private savers in rich countries that were not stockpiling reserves. Reserve managers did not finance any unmet needs. Rather, they distorted the U.S. economy and sowed the seeds of the (2008) financial crisis.

Reserve managers created two linked problems for the United States. First, the extra demand for dollar assets had to be matched by additional supply; Americans had to create more than $4 trillion in safe financial obligations. Second, governments accumulated their dollar reserves by suppressing domestic spending relative to domestic production. That exacerbated the global glut, particularly of manufactured goods. Someone had to absorb this excess production to prevent a global depression. The preeminence of the U.S. dollar meant that Americans were the ones who absorbed the bulk of both the excess capital inflows and the excess manufactured goods from the rest of the world. The consequences were the housing debt bubble and a displaced manufacturing base. Rather than an exorbitant privilege, the dollar’s international status imposed an exorbitant burden.” (p. 201-202)

America’s current account deficit hit 4 percent of GDP in the late 1990s for the first time since the 19th century. It expanded to 4.3 percent by 2003 and peaked at 7 percent in 2008, which helped create the distortions that led to the financial crisis. Since 2008, the current account deficit has persisted at about 2-3 percent of GDP yearly. This persistence can only be explained by excessive savings abroad. And given that a majority of that excessive savings seeks safe refuge in the American economy and financial system, either borrowing will rise, or income will fall.

“For example:

Net inflows into the U.S. can cause the dollar to become more expensive than it otherwise would be. Currency appreciation increases household purchasing power at the expense of export revenues and incomes, which means less saving through a combination of higher consumption and lower production.

Cheap imports can displace existing workers and raise U.S. unemployment. Unemployed workers have a negative saving rate because they still consume even if they have no income, which means that rising joblessness mechanically lowers the national saving rate.

Lower employment leads to additional government borrowing to fund larger fiscal transfers, most of which would have caused consumption to rise and savings to decline.

To reduce unemployment, the Fed might try to encourage additional borrowing through lower interest rates and looser credit conditions.

The combination of foreign inflows and the Fed’s monetary response can boost the prices of real estate, stocks, and other American assets to levels above where they otherwise would have been, even setting off asset bubbles. Higher asset prices make people feel richer and cause them to spend more out of their current income.

All of these mechanisms cause some combination of falling income (rising unemployment) and rising debt. Insufficient spending on goods and services by foreigners, in other words, necessarily translates into excessive purchases of American financial assets, thanks to the dollar’s unfortunate status as the premier international reserve asset, which then results in an increase in American debt.” (pp. 215-216)

VIII. What is the fifth top takeaway?

The Conclusion and What Can Be Done About It

“Trade war is often presented as a conflict between countries. It is not: it is a conflict mainly between bankers and owners of financial assets on one side and ordinary households on the other—between the very rich and everyone else. Rising inequality has produced gluts of manufactured goods, job loss, and rising indebtedness. It is an economic and financial perversion of what global integration was supposed to achieve. For decades, the United States has been the largest single victim of this perversion. Absorbing the rest of the world’s excess output and savings—at the cost of deindustrialization and financial crises—has been America’s exorbitant burden.” (p. 221)

So then, what can the United States do about it?

“In the short term, America’s first objective should be to shift the burden of absorbing unwanted financial inflows from the U.S. private sector to the federal government. American households and companies should not be pushed to borrow more than they can afford out of misguided concerns about the budget deficit or the level of government spending. As we have shown, the fact that the United States must absorb a permanent financial account surplus means that the only way to prevent rising American unemployment is with some combination of higher private borrowing and higher government borrowing. That is why, in the near term, U.S. Treasury debt should be issued as needed to accommodate the desires of foreign savers. Lower payroll taxes, larger standard deductions on income taxes, and a better social safety net, particularly for health expenses, would all help generate the necessary budget deficits while simultaneously ameliorating the unequal distribution of income.

It would be even better if the federal government absorbed foreign financial flows by directly or indirectly increasing investment in much-needed American infrastructure, particularly public transit and green energy. Many years of fiscal austerity and neglect have generated a large backlog of worthwhile projects. Moreover, infrastructure investment in the United States would almost certainly generate increases in debt-servicing capacity that substantially exceeded the additional debt-servicing cost, so it would not even result in a higher overall debt burden: debt would rise, but GDP would rise by more.” (pp. 226-227)

What about China?

“First, the hukou (or household registration) system should be reformed and eventually eliminated so that all Chinese can gain access to the government benefits they pay for with taxes regardless of where in the country they currently live. Second, the government should expand the quality of its safety net and guarantee reasonable income security in retirement, including health care. Third, the government should make it easier for workers to organize and negotiate better pay and labor conditions. Fourth, state-owned enterprises should pay higher dividends. Ideally, those dividends would be distributed directly to Chinese households through a dedicated social wealth fund. Fifth, the government should continue its efforts to improve air and water quality through tighter environmental regulations. Sixth, the government should reform its tax system by lowering the burden on the poor and middle-income consumers while raising taxes on the highest earners. Last, the government should continue to prop up the value of the yuan, including by selling foreign exchange reserves, if necessary, which would help shift purchasing power from the owners of exporting companies to regular Chinese consumers.” (p.229)

And then, what about Europe?

“The most practical solution is to federalize European fiscal policy as much as possible. National governments would spend less, tax less, and borrow less, thereby allowing them to honor their treaty commitments without turning the euro area into a permanent menace for the rest of the world. The European Investment Bank could become the main funding source for infrastructure projects across the bloc and could coordinate projects across national borders. Common deposit insurance and bank resolution would ensure that savings at banks in Greece and Portugal are always as good as savings at banks in Germany and the Netherlands. Finally, a new central euro area treasury would take over core spending functions such as unemployment reinsurance and retirement security, backstop the EIB, issue debt that would be as desirable for international investors as U.S. Treasury bonds, and levy common taxes. Ideally, those new taxes would crack down on corporate profit shifting within the currency bloc and target the net wealth of the richest residents of the euro area.” (p.231)

IX. What does The X Project Guy have to say?

This book was published in May 2020, just as the pandemic was getting underway. As we know since then, the US Government’s fiscal deficit spending exploded, causing inflation, which caused the Fed to aggressively hike interest rates, seemingly putting the United States firmly in fiscal dominance. I will be searching for any updates to the author’s thinking about their prescription for what the US should do to reduce the current account deficit and minimize the negative impacts of our exorbitant burden.

As for the Chinese prescription, there is good news as the authors point out that everything they suggested is not only known by the Chinese government but all but the last recommendation was officially proposed during the CCP’s Third Plenum leadership meeting in October 2013. A former governor of the Central Bank supported the last recommendation. Furthermore and more recently, since Xi Jinping’s ascension to a third term, Xi has emphasized a return to common prosperity for all as a goal for Chinese society, which seems supportive of the authors’ recommendations. However, powerful vested interests benefit from the status quo and are ferociously opposed to these reforms. If anyone can overcome that elitist opposition, it is Xi.

On the other hand, the European prescription is dead on arrival. The X Project does not see any way that individual European countries will cede their fiscal policies to a central European authority. The European Union will likely break up before that happens.

X. Why should you care?

Our current global trade, finance, and macroeconomic system evolved over decades, and it took decades for the distortions and imbalances to grow to this point. Unfortunately, the wealthiest global elites benefit most from this system and will not willingly agree to help change it to their detriment. So, what can we expect? More of what we’ve been experiencing, which, most importantly, is an increasing frequency of financial crises. And the responses to the financial crises we’ve experienced thus far in our lifetimes have only added to the distortions and imbalances. And that, too, is expected until we have a big enough crisis that completely breaks the system to a point that the only thing to do is to create a new, better system. There are many risks on this path, but also many opportunities. Many will suffer a lot of pain, but in the end, most will be much better off. We did something similar nearly eighty years ago after the painful crises of The Great Depression and the World Wars in Bretton Woods, which ushered in many decades of relative peace and prosperity.

To help you know what you need to know, please help ensure The X Project continues its mission.

Please hit the heart icon indicating you like this article

Please share this article (and prior articles) with anyone and everyone you know and care about.

Please consider a paid subscription. The paywall will go up in January, restricting each new article's final sections to paid subscribers only. Through 12/31/23, all paid subscriptions come with a free 60-day trial, and you can cancel at any time. All paid subscriptions in January will come with a free 30-day trial. Every month, for the cost of two cups of coffee, The X Project will deliver ten articles per month ($1 per article), helping you know in 1-2 hours of your time what you need to know about our changing world at the intersection of commodities, demographics, economics, energy, geopolitics, government debt & deficits, interest rates, markets, and money.

If you see value in the articles published so far and in the mission of The X Project, please be generous and aggressive in referring friends. Click the link to see the rewards where you can earn free paid subscriptions as well as the link to use for making referrals.