In this 12-minute article, The X Project will answer these questions:

I. Why this article now?

II. What is heliocentrism in the context of the energy transition?

III. Why is the global renewable energy transition characterized as linear rather than exponential?

IV. What challenges does increased reliance on intermittent renewables pose for grid reliability?

V. Why is electrification progressing slowly despite advancements in renewable energy?

VI. What role will natural gas continue to play in the energy transition?

VII. What is the current state and future outlook of carbon capture and storage (CCS) technology?

VIII. What are the implications of the gradual pace of the energy transition for policymakers and investors?

IX. What does The X Project Guy have to say?

X. Why should you care?

Reminder for readers and listeners: nothing The X Project writes or says should be considered investment advice or recommendations to buy or sell securities or investment products. Everything written and said is for informational purposes only, and you should do your own research and due diligence. It is recommended to consult with an investment advisor before making any investments or changes to your investments based on information provided by The X Project.

I. Why this article now?

Michael Cembalest of JP Morgan published “Heliocentrism,” his 15th annual energy paper, in March, and this article is long overdue. Cembalest “is the Chairman of Market and Investment Strategy at JP Morgan Asset Management. Since 2005, Michael has been the author of the Eye on the Market, which covers a wide range of topics across markets, investments, economics, politics, energy, municipal finance, and more.”

The X Project curates, summarizes, distills, and synthesizes knowledge and learning at the interseXion of economics, geopolitics, money, interest rates, debts, deficits, energy, commodities, demographics, and markets - helping you know what you need to know. I listed energy separately from the broader topic of commodities for a reason, given its importance to our future. So, it is time to catch up and provide additional coverage on that topic.

Here are the prior energy and energy-related commodity articles, in case you missed them before:

Article #21: Energy Transition Crisis - A summary of the 8-part docuseries by Erik Townsend

Article #23: Navigating the Tides of Black Gold - Exploring the Bullish and Bearish Perspectives in the Crude Oil Market

Article #46: Generational Opportunities: A Summary of "The Norwegian Illusion," GoRozen's Latest Market Commentary

Article #48: "Electravision": A Summary of Michael Cembalest's 14th Annual Energy Paper

Article #55: The Case for Uranium: Why it looks bullish and why we should embrace it?

Article #60: Electricity and the Grid - What you need to know and why

Article #65: What Does the IEA's Latest Crude Oil Report Tell Us? And should we believe it?

Article #72: What in the World is going on with Energy? Reviewing the Energy Institute's 2024 Statistical Review of World Energy

Article #97: “Bettering Human Lives”: Liberty Energy’s Report Providing Insight on Chris Wright’s Views

Article #99: Doom or Boom? Doomberg’s Energy Outlook

Article #114: The U.S. Goes Nuclear: Powering up America's Future

Given that energy is the foundation of life, our economy is essentially the transformation of energy, and it is the most critical prerequisite for prosperity and security, it is vital to have a comprehensive understanding of the topic.

II. What is heliocentrism in the context of the energy transition?

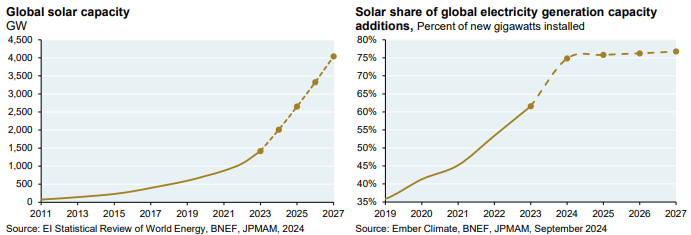

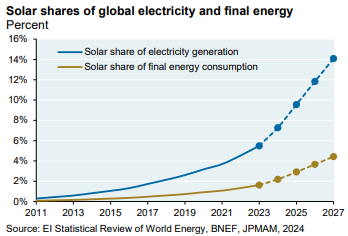

Heliocentrism, as used in this context, refers to the view that rapid growth in solar power and energy storage is central to the global energy transition, thereby minimizing the need for complementary thermal power generation. Proponents highlight the significant increase in global solar capacity, which has doubled over the past three years, with projections indicating continued substantial growth through 2027. This expansion has made solar power the dominant new electricity generation source, accounting for about 75% of expected new capacity by 2027.

However, despite rapid solar growth, its actual contribution to global electricity generation remains modest, projected to reach only around 14% by 2027 due to relatively low solar capacity factors of 15-20%. When considering broader final energy consumption, solar currently accounts for merely 2%, with expectations that it will double by 2027. Thus, while solar power is growing impressively, it still constitutes a relatively small portion of global energy usage.

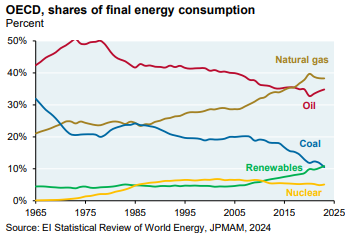

Furthermore, the energy transition towards renewables remains linear rather than exponential due to the continued reliance on fossil fuels in essential sectors, such as transportation and industrial manufacturing. The infrastructure and economic realities underscore a prolonged reliance on natural gas and other fossil fuels, suggesting that a pragmatic acknowledgment of ongoing fossil fuel dependency must temper heliocentric optimism.

III. Why is the global renewable energy transition characterized as linear rather than exponential?

The renewable energy transition is linear because the pace of replacing fossil fuels with renewable energy remains modest, improving by about 0.3%-0.6% annually in the renewable share of global final energy consumption. Unlike previous industrial transitions, such as innovations in steel production, which significantly improved productivity and energy efficiency, the renewable energy transition often lacks the dramatic economic benefits that inherently incentivize rapid adoption.

Historical transitions that progressed rapidly typically offered significant improvements in production efficiency and cost reductions, enabling new technologies to pay for themselves quickly. In contrast, renewable energy advancements, though environmentally beneficial, have required substantial global investments totaling approximately $9 trillion since 2010, without corresponding rapid economic payoffs. These significant upfront costs have kept the transition at a steady, incremental pace rather than enabling rapid acceleration.

Ongoing infrastructural and technical challenges also reinforce the linearity of the transition. Significant obstacles remain in electrifying sectors traditionally dependent on fossil fuels, such as heavy industry and transportation. Moreover, logistical issues such as transmission bottlenecks, transformer shortages, and prolonged permitting processes further constrain the pace, ensuring that the shift remains gradual and incremental.

IV. What challenges does increased reliance on intermittent renewables pose for grid reliability?

The increased reliance on intermittent renewables, such as wind and solar, poses substantial challenges to grid reliability due to their variable nature, making it difficult to match supply with demand consistently. Independent System Operators (ISOs), such as MISO and PJM in the US, highlight the risks of capacity shortfalls, especially during peak demand periods, due to insufficient backup and storage solutions, as well as the premature retirement of traditional baseload thermal plants.

For instance, despite considerable additions to battery storage projected over the next several years, experts caution that these may still be insufficient to ensure a continuous power supply during extended periods of low wind or solar output. Battery storage, while rapidly expanding, has limitations regarding duration and scalability, emphasizing the continued necessity for traditional thermal backup capacity to maintain grid stability.

Further exacerbating reliability issues are policy pressures leading to the closure of coal and natural gas plants without fully operational alternatives, underscoring the practical challenges of a rapid transition to predominantly renewable sources. These realities underscore the ongoing need for a careful balance between the expansion of renewable energy and the maintenance of traditional baseload capacities to ensure reliability and resilience.

V. Why is electrification progressing slowly despite advancements in renewable energy?

Electrification, despite significant advancements in renewable energy, progresses slowly due to several interrelated factors. Firstly, existing infrastructure, particularly in heavy industry, transportation, and building heating systems, remains deeply entrenched in fossil fuel usage. Many existing systems have long lifespans, and replacing or retrofitting these with electric solutions requires substantial capital investment and logistical coordination.

Secondly, economic barriers significantly influence electrification rates. Electricity often remains considerably more expensive than natural gas or other fossil fuels in many regions, particularly in the absence of robust carbon pricing mechanisms. This cost disparity hampers the economic feasibility of widespread electrification, discouraging rapid transition in sectors sensitive to energy costs, such as industrial manufacturing.

Finally, logistical and supply chain constraints further impede rapid electrification. Issues such as insufficient growth in transmission line infrastructure, transformer equipment shortages, and lengthy permitting processes collectively hinder efforts to electrify. These challenges underscore the complex and multifaceted nature of transitioning an economy's foundational energy systems, ensuring that electrification, while essential, advances incrementally rather than swiftly.

VI. What role will natural gas continue to play in the energy transition?

Natural gas will remain integral to the energy transition due to its essential role in providing reliable, dispatchable power, especially as renewable energy adoption grows. Given the intermittent nature of renewables, natural gas plants will continue to provide critical backup capacity, ensuring grid stability and reliability during periods of insufficient renewable generation.

Additionally, natural gas serves as a vital fuel source for heavy industry and specific transport sectors, where direct electrification or renewable alternatives are currently either economically or technologically impractical. Industries such as steel, cement, chemicals, and ammonia production heavily depend on fossil fuels for energy and raw materials, making natural gas indispensable for sustained industrial activity and economic prosperity.

Finally, geopolitical considerations also favor the continued use of natural gas. Regions like Europe and Asia, currently reliant on substantial fossil fuel imports, benefit strategically and economically from maintaining diverse energy sources, including natural gas, to mitigate energy security risks and buffer against disruptions in renewable energy supply chains.

VII. What is the current state and future outlook of carbon capture and storage (CCS) technology?

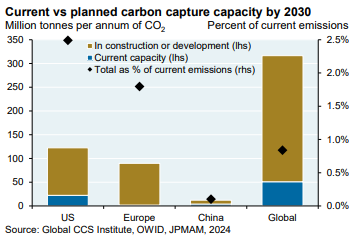

Carbon capture and storage (CCS) technology, despite extensive discussion and research interest, remains limited in practical application. Current and planned CCS capacities in the US and Europe represent only a minor fraction (approximately 2%-2.5%) of emissions, with historical CCS project completion rates notably low due to technological, economic, and regulatory challenges.

A core challenge for CCS lies in its economic feasibility and technological readiness, particularly for capturing carbon from power generation plants, which emit flue gases with relatively low CO2 concentrations. These technical hurdles significantly elevate CCS costs, deterring widespread adoption and limiting its role in global decarbonization strategies.

Despite these barriers, CCS remains a critical component in long-term decarbonization scenarios, especially for industrial sectors where electrification remains impractical. The future outlook will heavily depend on technological advancements reducing CCS costs, improved regulatory frameworks, and potentially increased carbon pricing, making CCS economically viable on a broader scale.

VIII. What are the implications of the gradual pace of the energy transition for policymakers and investors?

The gradual pace of the energy transition implies that policymakers must adopt realistic timelines and policies reflecting incremental progress rather than rapid transformation. Effective policies will require long-term planning, continued support for technological innovation, and targeted investments in infrastructure, particularly transmission and storage.

Investors, recognizing the prolonged transition timeframe, should maintain diversified portfolios that balance renewable investments with strategic positions in essential fossil fuel industries, particularly natural gas. Such a strategy will help manage transition risks and leverage ongoing economic dependencies on traditional energy sources.

Ultimately, both policymakers and investors should prepare for sustained, gradual progress rather than abrupt changes, recognizing that the energy transition involves complex socio-economic, technological, and geopolitical dimensions, demanding careful navigation and balanced strategies.

IX. What does The X Project Guy have to say?

The current narrative, as it relates to hydrocarbon-based energy, is that the United States is awash in supplies, and hence the low cost of crude oil and natural gas. While narratives and trends change, and the cure for low prices is indeed low prices, this narrative masks the problems that exist concerning our electricity supply and the challenges we face in addressing these issues.

While I understand the challenges that renewables pose to the stability of our electrical grid, I have installed an 11.5 kW solar array on my home, which covers approximately 65% of my electricity consumption. I took advantage of federal and state incentives such that my reduced electricity bill offsets the financing costs of the system. I consider this investment a hedge against future higher electricity costs. However, I also have a 20 kW natural gas generator for additional back-up as there is a real risk that we soon start experiencing electrical grid failures that disrupt something that most take for granted.

X. Why should you care?

Aside for the risk to your supply of electricity, the other reason you should care is the investment opportunity this situation presents. This is why I subscribe to the following investment themes and why the fourth, fifth, sixth and ninth are included in the list below:

Overweight cash and short-term U.S. T-bills for optionality, given expected INCREASING volatility related to the remaining list below.

Bullish gold and gold miner equities

Bullish Bitcoin

Bullish oil and oil-related equities

Bullish natural gas and related equities

Bullish uranium and related equities

Bullish industrial-associated commodities and equities

Bullish agricultural-associated commodities and equities

Bullish industrial and primarily electrical infrastructure equities

Bearish long-dated U.S. and other Western sovereign bonds

Remember, this is not investment advice nor recommendations to buy or sell securities or investment products. Everything written and said is for informational purposes only, and you should do your own research and due diligence. It would be best to discuss with an investment advisor before making any investments or changes to your investments based on any information provided by The X Project.

Thank you for your subscription, especially if you are a paying subscriber. Your support is everything to The X Project and is greatly appreciated. If you agree, please do me the favor of hitting the like button and posting positive comments about my articles, assuming you have positive things to say.