In this 14-minute article, The X Project will answer these questions:

I. Why this article now?

II. What is money?

III. What is a currency?

IV. What are the different types of money or currencies?

V. What is the difference between fiat and hard currencies, and what do we have today?

VI. How is fiat money created today?

VII. What is base money as opposed to broad money?

VIII. Why does this distinction matter in how money is created?

IX. What does The X Project Guy have to say?

X. Why should you care?

Reminder for readers and listeners: nothing The X Project writes or says should be considered investment advice or recommendations to buy or sell securities or investment products. Everything written and said is for informational purposes only, and you should do your own research and due diligence. It would be best to discuss with an investment advisor before making any investments or changes to your investments based on any information provided by The X Project.

I. Why this article now?

The X Project is knowledge & learning at the X of commodities, debts, deficits, demographics, economics, energy, geopolitics, interest rates, markets, and money. A couple of months ago, I wrote “What's Going on with Currencies These Days? An Introductory Primer to Foreign Exchange Markets,” referencing money as one of The X Project’s ten topics of interest. In doing so, I used the terms money and currency interchangeably, which is common despite having slightly different meanings.

Before my introductory article on foreign exchange markets, I had written a few articles on the dollar:

For this week’s article, I started writing an article on de-dollarization prompted by recent news that Chinese investors sold a record amount of U.S. assets in May. How that news is linked to de-dollarization made me realize that I need to explain several concepts that will take more than one article to explain. The concept of money, what we use as money, and the supply of that money is foundational to our economy and its financial system.

II. What is money?

I wrote an article, “Broken Money: Why Our Financial System is Failing Us and How We Can Make it Better - A summary of the book written by Lyn Alden” in which I covered five major themes or takeaways that did not include what money is. She wrote a great book containing nearly 500 pages of information, including the best explanations of money that I have come across. This article will lean heavily on her book.

The first section of her book, comprising the first four chapters and 59 pages, is called “What is money?” She delves into the evolutionary history of money, including the credit and commodity theories of money, to conclude with her own unified theory of money, which can also be described as a ledger theory of money.

“A ledger theory of money observes that most forms of exchange are improved by having a salable unit of account that can be held and transferred over both time and space, and that this unit of account implies the existence of a ledger, either literally or in the abstract. These monetary units and the ledger that defines them rely either on human administrators or on natural laws to maintain their stability across time and space.”

As an alternative, Wikipedia’s definition of money is

“any item or verifiable record that is generally accepted as payment for goods and services and repayment of debts, such as taxes, in a particular country or socio-economic context.[1][2][3] The primary functions which distinguish money are: medium of exchange, a unit of account, a store of value and sometimes, a standard of deferred payment.”

III. What is a currency?

Those definitions of money probably sound very abstract and theoretical. Most people think of money as the currency in their wallet, the amount in their bank account, the amount they owe on their credit card, and the amount they get paid.

Wikipedia’s formal definition of a currency is

“a standardization of money in any form, in use or circulation as a medium of exchange, for example banknotes and coins.[1][2] A more general definition is that a currency is a system of money in common use within a specific environment over time, especially for people in a nation state.[3] Under this definition, the British Pound sterling (£), euros (€), Japanese yen (¥), and U.S. dollars (US$) are examples of (government-issued) fiat currencies. Currencies may act as stores of value and be traded between nations in foreign exchange markets, which determine the relative values of the different currencies.[4] Currencies in this sense are either chosen by users or decreed by governments, and each type has limited boundaries of acceptance; i.e., legal tender laws may require a particular unit of account for payments to government agencies.”

That probably makes more sense. However, “fiat” currency is mentioned above. What does that mean, and are there other types of currencies?

IV. What are the different types of money or currencies?

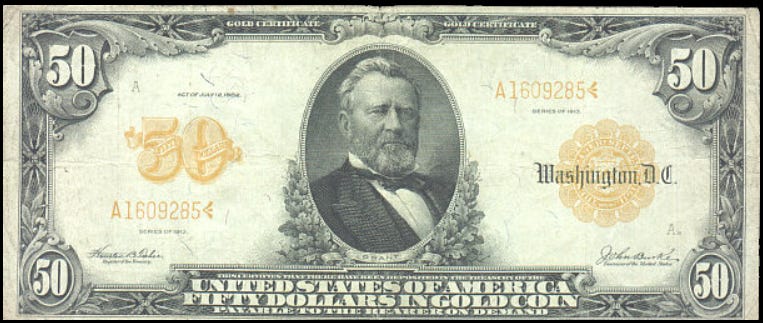

Before we define fiat money, let’s define commodity and representative money. Commodity money is simply money whose value comes from the commodity from which it is made. Think gold or silver coins. Commodity money has intrinsic value as well as transactional value. Representative money has no intrinsic value but represents something of value for which it can be exchanged. A good example of representative money is gold certificates, which may also then be considered commodity-backed money. These are both considered “hard” money because the money is either made from a hard, valuable commodity or it is backed by a hard, valuable commodity.

Fiat money, on the other hand, is not backed by any precious metal or any other hard, valuable commodity and therefore has no intrinsic value. Fiat money is simply a currency that is designated as money by fiat, or by a government decree.

V. What is the difference between fiat and hard currencies, and what do we have today?

Because hard currencies are backed by a valuable commodity or a precious metal - let’s use gold as an example, the amount of money is limited by the amount of the commodity. While gold is mined or produced continuously, annual production only increases the supply of gold in the world by 1-2% per year, thus constraining the growth of the money supply. Of course, even money made from precious metals can be diluted such that the supply of money is increased more rapidly. History is full of stories of governments becoming over indebted, “debasing” their currencies to create more money to pay off the debts, and ultimately leading to the failure of the currency and the failure of the government or empire issuing the failed currency. Only pure gold and silver has withstood the test of all-time history as money, and will continue to do so.

(For more information on gold, see the prior articles by The X Project:

Gold Prices are at New All Time Highs - Why now? And what does it possibly mean?

What’s Up with Gold? The Latest News, Analysis, and Thoughts on Gold

"The New Gold Playbook" - Reviewing Incrementum's 11th Annual "In Gold We Trust" Report)

The supply of fiat money has no natural constraints, and therefore the supply is prone to grow over time, diminishing the value of fiat money. Governments that issue fiat currency are more prone to indebtedness as our the society’s and the financial and economic actors that use fiat currencies. The symptom of this phenomenon is inflation. The more fiat currency that is created and in supply in the economy, then the more goods or services will cost assuming a fixed supply of those goods and services. As a result, all fiat currencies throughout history have ultimately failed, which has led to the failure or greatly reduced power of the empire or government that issued the failed fiat currency.

(For more information on the statements in the preceding and following paragraph, see these articles by The X Project:

The Price of Time: The Real Story of Interest - A summary of the book written by Edward Chancellor

Priced in Gold – Looking at Inflation, the Dollar, and the World from a Different Perspective

Since 1971 when the United States suspended the convertibility of its currency into gold, the U.S. and all currencies in the world today are fiat currencies, and all fiat currencies in existence today are in the process of failing.

VI. How is fiat money created today?

It is commonly assumed that fiat money is “printed” into existence. What does that really mean? 40 years ago when credit cards were far less common and debit cards did not exist yet, physical cash was a much bigger part of our economy. We saved money by depositing cash in a bank savings or checking account. When we had a large transaction for which cash was inconvenient or inappropriate or when we had so send even small amounts of cash to pay a bill, we would write a check that served as a certificate representing the cash in our bank account. We imagined banks having huge vaults filled with cash, and banks maintained the ledger keeping track of everyone’s cash.

We also borrowed money from banks to buy a car or a house. This is where things can get a little confusing. The loan you take out from a bank is your liability, but it is the bank’s asset. And the money you deposit at a bank is your asset, but the bank’s liability.

What was true then and has been true for centuries is that banks operate on a system of fractional reserves meaning they loan out more money (creating assets for themselves) then they actually have from everyone’s deposits (their liability). Banks only maintain a fraction of the reserves needed to cover their liabilities.

Generally speaking, this means that money is created whenever new debt is created, and consequently money is destroyed whenever debts are defaulted on or paid back.

But because we have a fractional reserve banking system and governments that continue to borrow huge amounts of money, there are a couple additional definitions of money we need to know and some important distinctions of how money is created.

VII. What is base money as opposed to broad money?

Quoting Lyn Alden directly from her book:

“The monetary base or “base money” is the foundation of the fiat currency system and consists of the combination of 1) physical currency in circulation, and 2) cash reserves that the commercial banking system holds with the Federal Reserve. This monetary base is a direct liability of the Federal Reserve.”

“Figure 15-A shows the amount of currency in circulation and the amount of reserves in the system. The combination of these two numbers represents the total monetary base since 1960.

As the chart shows, physical currency in circulation goes up in a rather smooth, exponential way. The amount of bank reserves used to go up at a similarly smooth rate until 2008 when it began to go up at a quicker pace due to the need for bank recapitalizations.”

“The broad money supply is far larger than the base money supply and represents money that the public holds. This broad money calculation consists of currency in circulation (which is also part of the base money calculation), but then also includes the massive amounts of checking deposits, savings deposits, and certificates of deposit that people and businesses hold at commercial banks (collectively referred to as “bank deposits”). As shown by Figure 15-B, what makes bank deposits different than physical currency and bank reserves, is that rather than being a direct liability of the Federal Reserve, they are instead a liability of a specific commercial bank.”

“Broad money represents the big set of money that people and businesses directly use to transact with each other, store our savings in, and define as our “money.” We often think that a dollar is interchangeable with another dollar, but really when we go from interacting with physical dollars to bank account IOUs, we switch from owning a direct liability of the Federal Reserve to a fractional claim for a direct liability of the Federal Reserve.”

“For both base money and broad money, most countries currently work the same way as the United States. A country’s central bank manages the base money of the system, and the commercial banking system operates the larger amount of broad money that represents an indirect and fractionally reserved claim to this base money.”

VIII. Why does this distinction matter in how money is created?

Continuing with Lyn Alden’s words directly:

“While the Federal Reserve determines the size of the U.S. monetary base, including what percentage of it may exist in the physical form of banknotes, changes in the amount of broad money in the system depend on forces outside of their direct control, such as government deficits and commercial bank lending practices. In other words, the Federal Reserve does not directly control the size of the broad money supply or the ratio of broad money to base money, even though they do control the amount of base money in the system. They can, however, influence the size of the broad money supply through their various monetary policy tools.

The purpose of modern commercial banks is to “multiply” base money into broad money and make a profit while doing so. We can call this the “money multiplier,” which is defined as the broad money supply divided by the base money supply. Figure 15-D shows the money multiplier since 1870.”

At the end of Lyn Alden’s 36-page chapter titled “How Fieat Currency is Created and Destroyed,” she summarized six ways money is actually created along with several observations which I have distilled to five as follows:

When banks make new loans, they increase the amount of broad money in the system (but not the amount of base money - although it does move those reserves around from one bank to another), and increasing the broad money supply can be inflationary. But because making new loans is simply increasing the leverage on the banks’ reserves, it is not quite “money printing” given possibility of loan defaults, liquidity requirements, and various regulations regarding how much leverage they can have. Making new loans increases the instability of the system given the fact that the banks provide the illusion of liquidity to an otherwise illiquid system where they do not have enough money available to cover their depositors’ accounts. “This illusion gets shattered every few decades, resulting in more base money being created to support the proliferation of these deposits.”

When the Fed creates new bank reserves (which it has the power to do), thus increasing the amount of base money in the system, and uses those new reserves to buy existing assets from banks, it does not increase the amount of broad money in the system. Instead, it de-levers banks and gives them more capacity to make new loans. Increasing the monetary base is “money printing” but in this case done not lead to an increase in broad money and therefore is generally not inflationary. This is the “quantitative easing” or QE that the Fed embarked upon in the aftermath of the Great Financial Crisis (GFC).

When the U.S. government runs a deficit, the U.S. Treasury injects banks deposits somewhere in the system. However, the government then sells bonds to cover that deficit. When nonbank entities buy those bonds, it is neither creating base money nor broad money because money is being extracted from the system to buy those bonds. However, it is displacing nonbank capital that might have otherwise been used more productively. This is referred to as the “crowding out effect.”

When the U.S. government runs a deficit and the U.S. Treasury sells bonds to commercial banks, it is a different story. The U.S. Treasury injects bank deposits that replenish the reserves that the banks used to buy the bonds, thus allowing them to buy more bonds. This increases the broad money and money multiplier (leverage ratio), and this can be rather inflationary if the banks have a lot of excess reserves to begin with.

When there is more supply of U.S Treasury bonds than there is demand from the public or from the commercial banks due to very large fiscal deficits and the Fed buys those excess bonds with newly created bank reserves out of thin air, then it is creating base money and broad money without extracting deposits from anywhere in the system. There is no limit to the extent that the Fed and Treasury can do this as it simply levers them both up, and this can be done regardless of whether the commercial banks lend or not. This is inflationary.

I normally keep this Section VIII behind the paywall for paid subscribers only. However, this is too important a topic and I want everyone to understand what was just explained. In the next Section, I will tell you what I think about all this. Then, in Section X, why should you care and, more importantly, what more can you do about it. However, I have just hit a new paid subscriber threshold, so you must now be a paid subscriber to view the last three sections. The X Project’s articles always have ten sections. Soon, after a few more articles, the paywall will move up again within the article so that only paid subscribers will see the last four sections, or rather, free subscribers will only see the first six sections. I will be moving the paywall up every few weeks, so ultimately, free subscribers will only see the first four or five sections of each article. Please consider a paid subscription.

Also, podcasts of the full articles narrated are available only to paid subscribers.

All paid subscriptions come with a free 14-day trial; you can cancel anytime. Every month, for just the cost of two cups of coffee, The X Project will deliver 6-8 articles (weekly on Sundays and every other Wednesday), helping you know in a couple of hours of your time per month what you need to know about our changing world at the interseXion of commodities, demographics, economics, energy, geopolitics, government debt & deficits, interest rates, markets, and money.

You can also earn free paid subscription months by referring your friends. If your referrals sign up for a FREE subscription, you get one month of free paid subscription for one referral, six months of free paid subscription for three referrals, and twelve months of free paid subscription for five referrals. Please refer your friends!